MONDAY, 25 NOVEMBER 2013

As children, we would have been accustomed to the games we played being far removed from our experience of the world. Whether it was buying properties and building hotels to bankrupt our opponents in Monopoly, aiming our missiles to sink aircraft carriers in Battleships, or even trying to fill our bellies in Hungry Hungry Hippos, the world our games were played in and the one we lived in were separate and distinct. Furthermore, the concepts and ideas in these games were never particularly complex and certainly stayed far away from themes that might scare away potential customers, such as nuclear physics or the Age of Enlightenment. It might be surprising then that a quiet revolution is coming to the world of gaming, especially boardgaming, in the form of games that dare explore deeper scientific ideas and experiences. These games are even becoming quite popular!In The New Science by designer Dirk Knemeyer, players are one of the great scientists working during the scientific revolution in 17th century Europe. In the game, players compete with their adversaries to test scientific hypotheses and make discoveries. These are then published as papers which the players use to network with the rest of the scientific world (their opponents). The player with the most prestige at the end of the game is appointed the first President of the Royal Society. The game features discoveries that follow the historical progress of knowledge in mathematics, biology, physics and astronomy with cards representing ideas such as the discovery of logarithms, or the laws of attraction. Make no mistake, playing the game is just as cut-throat as the real world of academic science.

If this experience is a little bit too close to your day job, you could try The Manhattan Project by designer Brandon Tibbetts, in which you lead a great nation’s atomic weapons programme in the hope of beating your opponents to research and build better bombs. For those who prefer to work together, there is always Pandemic by designer Matt Leacock, where you play a team of scientists, researchers and logistics specialists trying to contain the outbreak of four deadly diseases around the world and to eventually discover the necessary cures. These games might explore some very new themes compared to more classic games, but that doesn’t mean that nobody is playing them. The Manhattan Project and Pandemic are ranked 213 and 47, respectively, on the largest online boardgame database boardgamegeek.com, which allows players to rate over 60,000 games (including the hundreds of different versions of Monopoly).

Science and mathematics have not just influenced games in giving them new themes; behind the scenes, these disciplines have had a much more profound impact on game design and development. The principles and systems that underpin many new games can be traced back to mathematical ideas such as graph theory and combinatorics, and an elite group of game designers are in fact mathematicians by training.

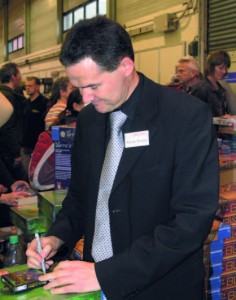

The name Reiner Knizia might not be recognised by most people, but he could very well be considered the Issac Newton of the boardgaming world for his incredible contributions and output. Over a period of 20 years, Knizia has created over 500 published designs, with sales exceeding 13 million games and books worldwide. But before this, Knizia graduated from the University of Ulm with a Diploma of Mathematics, before going on to gain a Master of Science from Syracuse University and a PhD in Mathematics from the University of Ulm. Furthermore, he has stated that his design approach stems in some way from his scientific background and that his games rest on fundamental principles such as risk, probability and optimisation, that he is so familiar with from his earlier studies.

Another mathematician-turned game designer is Richard Garfield, who is primarily known as the inventor of the trading card game Magic: The Gathering. He actually developed the game during his graduate studies in combinatorial mathematics at the University of Pennsylvania, with his fellow students acting as play- testers for the game. Not predicting the game’s future success, Garfield took up a position as Professor of Mathematics at Whitman College, Washington in 1993, the same year Magic was released. However, he ended up leaving academia altogether the following year once the game took off. Like Knizia, Garfield has spoken about how his background inspired him to design a game that involved both strategy and chance and how the combination of these two principles led to an engaging game. Considering that 20 years and over 10,000 unique cards later Magic is still going strong, it seems that a more scientific approach to game design might be the secret to their success.

Science has influenced both the themes and appearance of games, as well as their construction, but it is now also enabling the emergence of entirely new forms of games. With the prevalence of smartphones and GPS access, these scientific and technological developments are spawning a new class of location-based games, far beyond the simple checking-in at a location such as that seen in Foursquare. One of the pioneers in this field is Geocaching, in which players first hide ‘caches’ (usually small plastic boxes filled with a logbook and various other small items) anywhere in the world and then post the GPS coordinates of the cache’s location on a website, geocaching.com. Other players can then log on to the website, get the coordinates and try to find the cache, signing the logbook for posterity when they do and sometimes swapping an item that is in the cache. There are even specific items with barcodes that can be tracked as they move from cache to cache, sometimes circling the globe via the hands of multiple willing geocachers. Recently, even Google entered the arena with their world domination game Ingress. Players are split into teams with the goal of claiming portals, which are real world locations tracked via a smartphone. Linking the captured portals creates control fields which earns ‘Mind Units’ depending on the regions’ population. These games are only the beginning of what is possible, and this style of real world, immersive experiences may be giving us a glimpse of the gaming of the future. In any case, the myriad possibilities available by mixing existing analog and digital game forms, as well as entirely new technologies based on virtual realities, mean the gaming revolution is far from over.

Matthew Dunstan is a 3rd year PhD student at the Department of Chemistry