FRIDAY, 25 NOVEMBER 2011

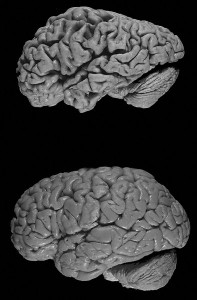

Alzheimer’s disease, the leading cause of dementia, affects about half a million people in the UK alone. It is a neurodegenerative disorder in which brains cells progressively die off. The resulting atrophy leads to impaired cognition with sufferers showing reduced ability to remember, perceive, judge and reason. However, in some cases the onset of symptoms can be delayed, even following severe physical deterioration of the brain.Bialystok and her colleagues in Toronto have previously shown that speaking two languages can delay the onset of Alzheimer’s symptoms by up to 5 years. Their new research used CT scans to study differences in brain anatomy between monolingual and bilingual Alzheimer’s patients. The two groups were carefully matched for age, years in education and, most importantly, cognitive ability. The study showed that the level of brain atrophy was greatest in the group of bilinguals, despite them having the same level of cognition as the monolinguals. This anti-correlation between atrophy and cognitive impairment suggests that speaking another language may help to protect against the effects of brain wasting.

The authors of the study propose that the ability to suppress one language whilst speaking another requires a great deal of brain power and could “train” up a so-called “cognitive reserve”. This reserve could be used to prevent a decline in mental ability despite increased brain cell death. At present, Alzheimer’s remains incurable and much work is focused on drugs that delay the onset of the disease. This study suggests that training your brain through intellectual activities might also be important in delaying the onset.

Written by Nicola Stead