WEDNESDAY, 15 MAY 2013

2013 marks the 100th anniversary of the Medical Research Council (MRC). Many have heard of this iconic institution, but few might realise the impact its research has had on our daily lives. This year, the MRC will be opening its doors to members of the public to reveal some of the life-changing research programmes that it funds. An emphasis on collaboration is a running theme, with many of their most recent discoveries being carried out in collaboration with the Welcome Trust, Cancer Research UK, or with one of the many other funding bodies in the UK. But it hasn’t always been this way.The MRC grew out of the Royal Commission to research the most pressing medical problem

in the UK in the early 20th century: tuberculosis. Funds came from the 1911 National Insurance Act. The money was to be spent on research carried out by investigators in approved institutions, the first science institutes in the UK. The first of these continues today in North London as the National Institute of Medical Research. In 1913, 100 years ago, the Medical Research Committee and Advisory Council was established. This was the single research organisation for the UK, developing and funding their own research programmes and providing funding for research by other individuals or institutions that complemented their own.

Today, the MRC is a non-departmental public body funded through the government’s science and research budget. There are 56 research establishments across the UK and Africa. The MRC supports research in all areas of medicine. Last year alone, the MRC funded 1,100 grants totalling over £309.9 million. In Cambridge, the MRC is currently committed to awards totalling over £130 million. It provides around 700 jobs in Cambridge at the MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology and its other units and many more through the grants held in the University of Cambridge, and other local research institutes.

The MRC has a long history in Cambridge. In 1944, the MRC set up the Applied Psychology

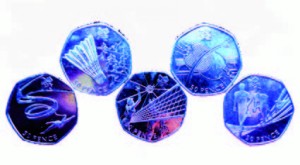

Research unit with Cambridge University’s Department of Psychology. The unit made advances in the field of service personnel research, such as the selection of aircrews, pilot fatigue and the design of aircraft controls and instruments. After the war it made a number of major contributions to our understanding of such psychological processes as attention and memory and continued to tackle practical problems. For example, the unit was responsible for the heptagonal shape of our 20p and 50p coins. Research into the lives of the blind or partially sighted revealed that a range of entirely circular coins were incredibly difficult to tell apart by touch, leading to much frustration for the partially sighted. The introduction of the heptagonal coins removed much of the difficulty, as each British coin is now distinctively different to both sight and touch. In due course, it was renamed the MRC Cognition and Brain Sciences Unit. This more modern counterpart is engaged in active collaborations with many other research institutes, and uses a range of brain imaging techniques.

Other major contributions in Cambridge by MRC units over the years span such fields as nutrition, protein engineering and cancer, covering topics as diverse as the biology of mitochondria, and the contribution of genes and lifestyle to the incidence of diabetes across Europe. One of the most exciting breakthroughs was the discovery of the helical structure of DNA by Watson and Crick in 1953 in what is now called the MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology (LMB). With the invention of DNA sequencing techniques by Fred Sanger, also at the LMB, the stage was set for the human genome project, with the Cambridge contribution led by John Sulston who moved from the LMB to found the Wellcome Trust supported Sanger Institute, where much of the UK effort was undertaken.

To coincide with the centenary, change is happening for the MRC. In Cambridge, the new

building for the LMB is complete, and research groups have been moving in since February 2013. The previous building was opened by the MRC in 1962, and was home to 9 Nobel Prizes, shared between 13 scientists at the LMB. As a result, the institute was nicknamed ‘The Nobel Prize Factory’. The new building is the flagship building for the extension of the Cambridge Biomedical Campus and the MRC hopes that it will continue to provide first class facilities to some of the world’s leading scientists. The laboratory will have cost £212 million, and will provide space for more than 400 researchers. The overall structure of the new building is evocative of paired chromosomes, with two long laboratory areas joined by a large entrance hall, containing seminar rooms and a lecture theatre. In keeping with the concept of partnership, the University have contributed towards the cost of the building, which will also house several University research groups.

Some may argue that not much has changed since the Royal Commission; the aim of the MRC

remains first and foremost the furthering of medical knowledge and understanding through scientific research. The biggest change in the last 100 years has been an increase in collaborations between research bodies. The MRC was founded as the first research body of its kind, but today, there is a wealth of research funding institutions, including sister research councils to the MRC. In Cambridge, the MRC works very closely with Cancer Research UK, the British Heart Foundation and the Wellcome Trust. Adrian Penrose, Regional Communications Manager for Cambridge and the Midlands has described it as a “catalytic coming together of scientific expertise”. With the complexity of the research questions to be addressed, and the need to bring together scientists from across the biological, physical and social sciences, collaborations have become invaluable. Expertise and experience are now found in a wide range of locations, and it is only by pooling knowledge and financial resources that research can be done effectively.

The MRC’s centenary year will be a way of emphasising these collaborations. As it moves

into its next 100 years, the MRC is embarked in a new form of collaboration, the ‘university units’, to strengthen the ties between the MRC and their academic research colleagues. As well as collaborations with universities, the MRC is also developing more collaborations with industry. The latter has had less money to spend on research, which has spurred on partnerships between industry and research bodies. This is particularly the case in the field of pharmacology, not least as a number of the expensive drugs are starting to come off patent. Late in 2012, the MRC announced a deal with AstraZeneca, a large UK pharmaceutical company. The company agreed to allow scientists access to certain compounds that did not go all of the way to becoming patented drugs. These compounds might nevertheless be useful for a different research area. Access to data from the pharmaceutical industry can, if shared, save valuable time and money, and allow scientists to make new discoveries.

The centenary year will be used by the MRC to extend their reach to a wider community. The MRC units regularly take part in the Cambridge Science Festival, and in June they will open their doors in the first MRC open week. More than 40 units and centres will be open to the public, some for the first time, so that members of the public can see for themselves the work carried out by the MRC.

Felicity Davies is an MPhil student at the Faculty of Philosophy