SATURDAY, 11 FEBRUARY 2012

Mental health disorders are a major cause of disability worldwide. Whilst treatments exist, they often have serious limitations, including unpleasant side effects and slow therapeutic responses of several weeks to months. They are also often associated with substantial failure rates with only a minority of patients responding to the drugs prescribed. Part of the problem is that drugs used to treat many psychiatric disorders offer symptomatic treatment rather than curing the disease. Antidepressants such as selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors (SSRIs), of which Prozac is a member, are often used in the treatment of depression, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and obsessive- compulsive disorder (OCD). Though these drugs are effective antidepressants, their efficacy in other disorders is limited. Moreover, Prozac was released in the US in the late 1980s and though a plethora of newer SSRIs have followed, all are variations on an old theme. Recently, scientists have begun to explore the potential of hallucinogen-induced states of altered consciousness in the hopes of finding better treatments for patients suffering from disorders where no effective therapies exist.In the last few years, scientists have begun to explore the potential of MDMA and psychedelics as adjuncts to conventional psychotherapy. Results from several pilot studies show that these substances increase empathy and facilitate the discussion of painful experiences. MDMA, otherwise known as ʻecstasyʼ, is an empathogen-entactogen (a class of drugs producing feelings of empathy, love, and emotional closeness to others) whose effects include euphoria, reduced fear and increased empathy and interpersonal trust. Classical hallucinogens (LSD, psilocybin from ʻmagic mushroomsʼ and mescaline from peyote cactus) induce in patients ʻmystical-likeʼ experiences, producing rapid and enduring positive changes in mood and behaviour, something that conventional medicine takes years to achieve. Ketamine, sometimes classed as a psychedelic, has recently been shown to act as a rapid antidepressant.

The re-emergence of psychedelics as medicines is not without controversy, as these are illicit substances associated with the hippie counter culture of the 1960s. Media sensationalism and public misconceptions surrounding these substances have prevented real scientific investigation into their mechanism of action, so little is known about their effects. Evidence-based medicine dictates that the merits of these drugs ought to be tested in scientific trials before making judgments.

Indeed, reports on hallucinogen research dating from the 1950s, such as the use of LSD by the British psychiatrist Humphry Osmond in the treatment of alcoholism, has shown these drugs to be beneficial tools in assisting psychotherapy. Sadly, promising psychedelic research ground to a halt in the 1970s when the uncontrolled use of LSD associated with its popularisation in the 1960s resulted in media scares and the drug being banned worldwide. MDMA was later similarly banned.

Forty years on sees the revival of a long-dormant research area. A pilot study in late 2010, conducted by Charles Grob and colleagues at Harbor-UCLA Medical Center, investigated the effects of a single dose of psilocybin in 12 anxious and depressed patients with advanced-stage cancer. A moderate dose of psilocybin produced a powerful and sustained improvement in mood, sometimes lasting up to a year. Another 2010 pilot study by Michael Mithoefer, this time focusing on PTSD patients, demonstrated that MDMA- assisted psychotherapy produced statistically significant improvements in symptoms, with 10 out of 12 patients reporting improvement compared to only 2 out of 8 for the placebo group. This effect lasted for up to two months and no drug-related adverse effects or neurocognitive deficits were associated with MDMA use. This study suggests that the moderate and infrequent use of MDMA in a controlled, clinical setting can be administered to PTSD patients without evidence of harm, which may render it an effective candidate in the treatment of a disorder that currently has no cure.

Remarkably, the reported mood-elevating effects of these drugs are immediate, require only one to two sessions and persist long after the acute effects of the drug have subsided. This is in contrast to conventional psychotherapy, which often takes years to achieve the desired effects. In a study published a few months ago, MacLean and colleagues found that a single high dose of psilocybin led to increased openness in healthy adults that, for some, lasted over a year. Hallucinogens might produce positive changes in personality by inducing mystical experiences, described as a ʻprofound and enduring sense of the interconnectedness of all people and thingsʼ. Such an experience is thought to enable individuals to transcend their usual patterns of thinking, feeling, and acting and thus induce increased feelings of openness.

Based on the promising results generated by this new wave of psychedelic research, a trial to study the effects of MDMA-assisted psychotherapy in PTSD patients is currently being planned in the UK. Its aim is to replicate the study by Mithoefer in the US and will be the first clinical trial to use MDMA in the UK. David Nutt, based at Imperial College London, and Ben Sessa, a psychiatrist based in Taunton, are two researchers involved in the study. In a phone interview, Dr Sessa said he hoped that the study would further explore the potential of MDMA as a therapeutic adjunct to PTSD psychotherapy. By using a larger group of patients and, in particular, using neuroimaging to explore the physiological effects of the drug, Sessa and colleagues hope to measure observable brain changes in blood flow before and after the MDMA treatment, which will help to better determine the effects of MDMA in the brain.

Sessa believes that MDMA could be an invaluable tool in the treatment of psychiatric disorders because, in carefully controlled settings, it allows trauma patients, with only one or two sessions of MDMA, to access painful, emotional material and talk about their experiences without being overwhelmed by negative emotions. SSRIs and conventional psychotherapy take much longer and require chronic administration to achieve the same effect, and importantly, do not treat the core root of the problem: access to repressed and painful memories. Eventually, Sessa hopes to see these drugs become mainstream therapies in the treatment of PTSD and various other disorders including OCD, depression, anxiety and substance abuse.

Unlike many illegal drugs, MDMA and psilocybin are not known to be addictive, but taken in uncontrolled settings MDMA can present with adverse effects including hyperthermia (elevated body temperature) and impairment of the kidney’s normal water homeostasis mechanism, whilst hallucinogens like psilocybin can sometimes cause extreme anxiety, and in rare cases, psychosis. Unlike for therapeutic purposes, MDMA taken recreationally in large quantities is thought to damage serotonergic neurons in the brain but the evidence is inconclusive, as results from animal studies are not easily extrapolated to humans – very large doses of MDMA are required to produce neurotoxic damage in the rat brain, which may not be representative of the smaller doses taken by recreational users. Though it will take some time before MDMA is introduced into the clinic as long-term effects in the brain remain to be investigated.

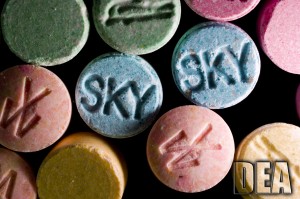

MDMA’s illegal status renders it almost impossible to assess its neurotoxicity in humans as the lack of knowledge about the dose and purity of street ecstasy consumed (since it is often mixed and may contain no MDMA at all) often distort results of cognitive performance in humans. A 2011 paper by Halpern et al found no association between ecstasy use and lowered cognitive performance and suggests that previous studies investigating the neurotoxicity of MDMA sampled ecstasy users who are often long-term, poly drug users consuming contaminated street drugs. These confounding factors often distort results of cognitive function and render them incomparable to pure MDMA taken for therapeutic purposes in moderate doses in a safe, clinical setting.

All medicine involves risk-benefit assessment and so, as with all drugs, Sessa wants an evidence-based rather than a socio-political approach to these substances. He feels that studies demonstrating a neurological explanation of what is happening and thus providing a clearer explanation of how these drugs work will give more validity to the studies and will perhaps help fight media and public misconceptions about the use of these drugs in therapy. Perhaps we should look past the preconceptions of the ʻpsychedelic 60sʼ and focus on the promising results arising from this new wave of psychedelic research.

Written by Camilla dʼAngelo.