FRIDAY, 27 APRIL 2012

In the last 20 years, medicine and neuroscience have made great strides towards a better understanding of the brain and improved treatment of mental health disorders. These achievements have been accompanied by a host of socio-economic effects. We have witnessed, for example, a reduced stigma associated with mental health disorders and their treatment. However, we have also seen an increase in the non-medical use of drugs, in particular the advent of cognition enhancers. These ‘smart drugs’ can help us to focus, learn and think faster. They are altering the way we perceive the medicinal purposes of drugs and may one day revolutionise the way we behave as a society.Cognition enhancers are most commonly used to treat cognitive impairments. These are associated with age-related neurological disorders, such as Alzheimer’s disease, and certain psychiatric conditions, including schizophrenia and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Common enhancers include the stimulants methylphenidate (Ritalin) and amphetamine (Adderall) used to treat ADHD, and modafinil, a newer drug currently prescribed for narcolepsy, a disorder leading to excessive sleepiness.

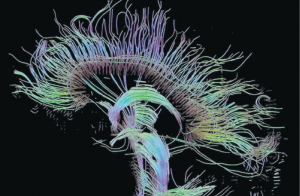

The known pharmacology of these drugs is relatively limited but they are widely thought to affect the so-called monoamine neurotransmitter system, which is important in regulating mood, cognition and reward. By modulating levels of dopamine and noradrenaline in the brain, these drugs act to improve attention and working memory, the aspects of cognition mediated by an area of the brain called the prefrontal cortex.

Drugs that enhance brain performance were originally developed to improve patients’ quality of life, as well as reducing long-term healthcare costs associated with treating an ageing population. However, it seems that cognition enhancers such as modafinil are increasingly being used by the healthy. In particular, university students have reported using stimulants like amphetamine and methylphenidate to help them work better and stay awake longer, in the hopes of giving them a competitive edge over their peers. Similarly, business people are believed to be using them to achieve improved performance in the boardroom.

Drugs such as modafinil that enhance brain performance with only a few side effects will have significant implications for society and may one day be used in a range of professions, such as military roles, air traffic controllers and surgeons. In such roles, fatigue is known to impair human performance and pharmacological enhancement could help. A 2011 study led by Barbara Sahakian investigated the effects of 200 milligrams of modafinil on the cognitive performance of sleep-deprived doctors and found that the drug significantly improved cognitive flexibility and reduced impulsivity. The result is promising and suggests that in the future doctors may benefit from modafinil enhancement, perhaps replacing the current most popular drug of choice, caffeine, which can have many side effects including anxiety, tremor and nausea.

Studies such as this one lead to the question of whether the future should see drugs like modafinil become available to any healthy individual wishing to enhance their cognitive capacities. The controversy surrounding the use of such ‘mental cosmetics’ to optimise brain performance in the healthy is that they constitute enhancement rather than therapy. Our current normative medical paradigm advocates therapy, which aims to fix people who are unwell by curing injuries and diseases. Enhancement, on the other hand, can be defined as improving people beyond their normal, healthy state. The problem is that defining whether an intervention constitutes therapy or enhancement can sometimes be difficult and even arbitrary.

For instance, a better understanding of the brain and the destigmatisation of mental health has been met with the diagnosis of novel disorders and increased use of drugs by people who would not have been considered ill twenty years ago. Statistics suggest that the antidepressant Prozac has become a part of life for many, not only as a treatment for depression but also as a mood enhancer, suggesting that the drug is able to improve aspects of people’s personalities not classed as part of their illness. Excessively active children are diagnosed with ADHD and novel drugs are available for people who suffer from extreme shyness (social anxiety disorder). These examples help to illustrate the fine and sometimes arbitrary line between illness and extreme traits. So rather than be solely devoted to curing illness, medicine could help us live better and achieve our goals by enhancing our health, cognition and emotional well-being beyond today’s norm.

The use of pharmacological cognitive enhancers has led to moral concerns that it is unnatural, cheating and equivalent to drug abuse. Fears have been raised regarding the potential of enhancing drugs to undermine the cultural emphasis on the value of hard work. However, caffeine is an example of a drug that is considered legitimate as an enhancer of alertness and performance. There is the potential for drugs with similar effects to become established in society in the same way as the caffeine in coffee. Therefore considerable debate exists over whether enhancing drugs could be as acceptable as non-pharmacological ways of improving cognitive importance.

As we witness a blurring between treatments and lifestyle drugs, concerns about the impacts of the increased medicalisation of society are rife. Those who prefer not to enhance their brain fear future coercion, both direct and indirect, into taking drugs merely to fit the social norm. Others worry that if cognition enhancers do become widely accepted we may become a ‘24/7’ society, with increased pressure to perform better by employers who expect pharmacologically-enhanced employees, akin to having the right qualifications today. There are also concerns that if enhancement is dependent on wealth this may lead to greater inequality and so fair access must be ensured.

As with all medicines, an evidence-based approach to assess the harms and risks of cognitive enhancers should be taken. Society has much to benefit from cognitive enhancement if the risks are managed correctly. If society accepts future enhancement, adequate policies should be put in place to protect individuals from coercion and promote fairness, such as ensuring universal access in schools. If we are to embrace this new technology, assessment of long-term health risks and the development of safe cognition enhancers will be imperative, including addressing their potential for abuse.

Modafinil use by the healthy appears set to increase but there is already considerable research into other types of cognition enhancers. For example, drugs known as ampakines, originally developed to treat schizophrenia, have also been shown to improve attention and memory in healthy individuals. The development of such enhancers is imperative as studies into their effects show great potential in the treatment of mental health disorders. A key challenge for use in the healthy will be to ensure responsible use and their careful evaluation to ensure safety.

However, status quo bias, a cognitive bias that renders people aversive to change, affects social attitudes to human enhancement and so stigma associated with the development of mental cosmetics to improve the lives of healthy individuals remains strong. Enjoying over-the-counter cognition enhancers, much like high-caffeine drinks in supermarkets, today does not seem so futuristic. Changing social landscapes and public perception may well pave the way for enhancement of the human condition through science, although the question of whether such enhancement is for the better of mankind still remains.

Camilla d’Angelo is a 1st year PhD student in the Department of Experimental Psychology