TUESDAY, 25 NOVEMBER 2014

The surprising answer can be, ‘Not that much’.In August 2014, neurologists Feng Yu and colleagues published a case study in the journal Brain. Their 24-year-old patient had been admitted to hospital for severe nausea lasting for over a month, and also reported an inability to walk steadily, which had continued or most of her life. A battery of scans revealed that she was missing an entire brain region, the cerebellum. She was diagnosed with cerebellar agenesis, meaning that the cerebellum had failed to form during the earliest stages of brain development.

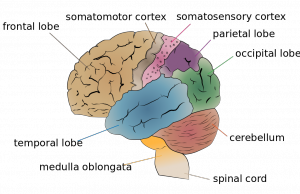

Cerebellar agenesis is an extremely rare condition. Few cases have been reported, and fewer have been diagnosed while the patients were still living; most are found at post-mortem. (Yu and colleagues’ report brings the total published number of living cases to nine.) This rarity is thought to be because the cerebellum – despite its small volume compared to other brain structures like the cortex – contains nearly half the nerve cells of the entire brain, a number around 85 billion.

The symptoms of the 2014 patient were comparatively mild. Her parents reported a delay in learning to walk and speak, her speech when admitted to hospital was ‘slightly slurred’, and she did have a consistent and prolonged difficulty walking. This is in keeping with the cerebellum’s known functions in controlling voluntary movement and learning new motor patterns. Otherwise, though, her daily life was normal: she was able to live independently and was married with a daughter.

This picture of a reasonably simple but independent life is similar to that of the other adult patients reported with cerebellar agenesis. It is, however vastly different from the prognosis for damage to an intact cerebellum in adult life. This can lead to disabling motor and cognitive impairment, epilepsy, or sometimes a potentially lethal build-up of fluid in the brain. Cerebellar agenesis may therefore be proof that the developing brain is even more resilient than we previously thought - and, as the researchers Lemon and Edgely pointedly suggest, that the supposedly ‘normal’ population does not use its 85 billion cerebellar neurons effectively enough!

Further reading

The 2014 case study

Lemon and Edgeley's review of 'Life without a Cerebellum'