SUNDAY, 9 MAY 2010

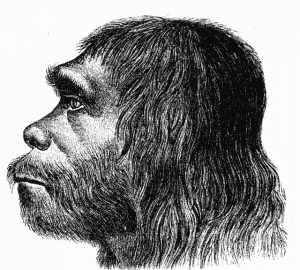

Researchers at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig have completed a four-year analysis of over one billion DNA fragments from 38,000 year-old Neanderthal bones. The team had to use some completely new techniques to identify Neanderthal DNA amongst the DNA of microbes that had colonised the remains. They managed to recover over 60 per cent of the Neanderthal genome.Comparison of the genome with that of modern humans reveals more similarity with Europeans and Asians than with Africans. According to Svante Paabo, who led the research, this suggests interbreeding in the Middle East between 100,000 and 50,000 years ago: "Neanderthals probably mixed with early modern humans before Homo sapiens split into different groups in Europe and Asia." The team calculate that between one and four per cent of DNA in modern non-Africans originated from Neanderthals.

Differences between the genomes have also allowed identification of several genes that may have been important in the survival and evolution of Homo sapiens over the Neanderthals, including some involved in cognitive function, metabolism and skeletal structure. Paabo is optimistic about the impact of future work: "We will also decode the remaining parts of the Neanderthal genome and learn much more about ourselves and our closest relative."

Written by Ian Fyfe